Roman Construction in Britain

These small posts dotted the wall every 100 yards or so. A system of manned stations that ensured reliable communication and support along the whole of the wall.

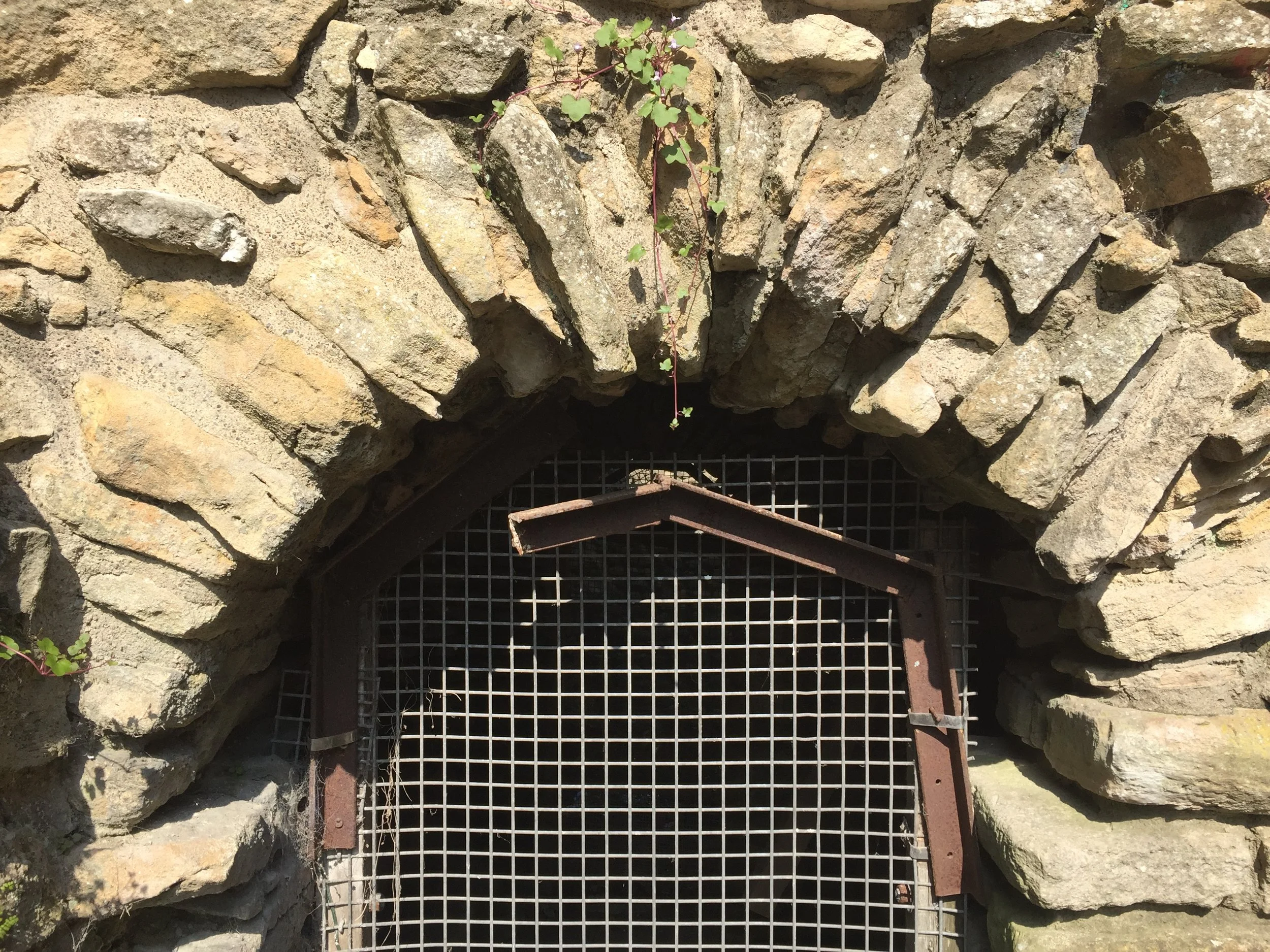

Note the wonderfully rough and practical stone arch! This was a frontier fort at the farthest reaches of the Empire. Far from polished, but by God it got the job done. Also, notice on the top right corner the revealed brick barrel vaulting. Apparently the soldiers wanted their vault and floor above to achieve a more precise, even surface. The land around York is peat. These red clay bricks must have been imported from farther south and used only in key areas of the fort.

Rough and rubble stone infill of the original Roman wall round York. This now revealed interior would have been encased by cut stone blocking. Note the scrap brick pieces thrown into the mix. Coming across such a sight brings these near abstract constructions vividly to the fore of my tangible experience.

Running my fingers across the odd brick here and there, I instantly relate to the men working here 2,000 years ago. Waste not, want not. Save the scraps and rubble for infill. This is a frontier fort, make the best use of what you've got. Slop in buckets full of mortar and then throw down the next course of infill. Work hard, work effectively.

Panoramic shot of a remaining Roman multangular tower. One of these was constructed on each corner of this fort. Each side of this fort was roughly 1/4 miles long. Notice the putlog holes to provide for a platformed floor. The band of brickwork is also visible on the outside of the tower. Apparently, some folks believe the brick to be a sort of leveling/strengthening method. But it strikes me as more likely a decorative veneer course. A band of red color, a symbolic bit of the Roman way weaved into the construction. If this brick was indeed imported then a solid band of brick would be quite costly for little gain. I could be wrong through, thoughts?

Note, the top most section of stonework (lighter colored limestone and archer slits) is a medieval addition. The stone sarcophagi are Roman.

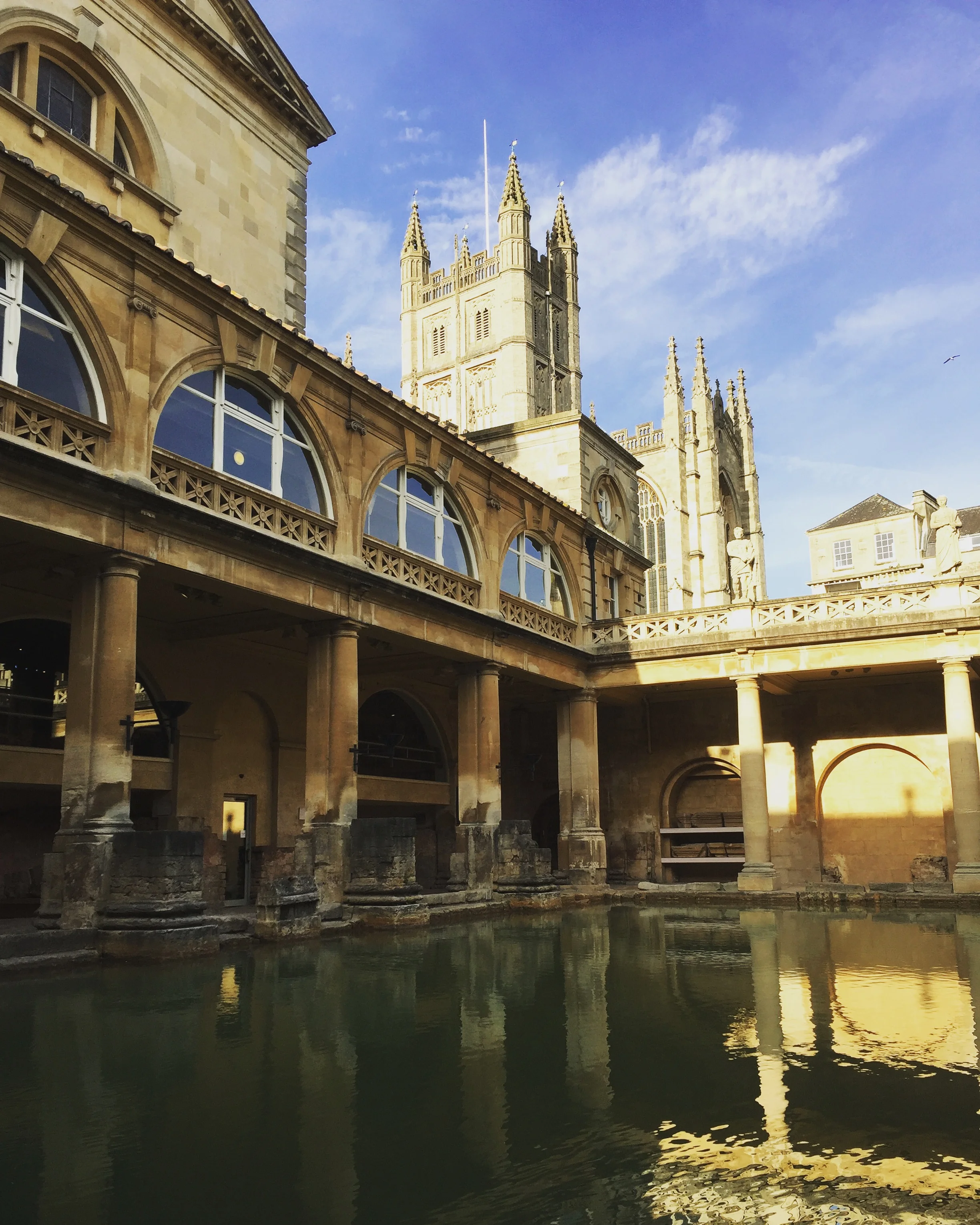

This Roman bath is fairly rare because it sits directly on top of a natural hot springs, the only one on the whole island in fact. Water flowing up today is 10,000 years old rainwater that fell atop the nearby Menslop hills and seeped its way down deep into the Earth. Eventually, the Earth internal heat and pressure forces the rainwater back up through cracks and fissures that wonderfully lead to this central hot spring.

The old bath and temple complex of the Roman outpost Aquae Sulis. The complex is nearly 2,000 years old, and it served the Roman Empire and her people for over 300 years. After the Romans receded from the island, the site fell into ruin and was submerged in silt for 1,400 years. In this picture the pool, lower sections of columns and walls are of Roman male, the balconies and adjoining building are later 19th century construction, and the Abby church in the background is late medieval. Roman structural masonry is still going strong!

The main pool of the Roman bath complex still holds water just as well as it did 2,000 years ago. The stone masonry pool is lined with a 2-3" thick sheet of lead. This lead lining is still in place and is the sole reason that water remains in the pool and at its original waterline! The entire sheet is calculated to weigh a sturdy 9.5 tons.

Original lead piping still sitting in its original channel. Setting aside the terrible health problems caused by fabricating all of your interior plumbing with lead, talk about staying power! These pipes serviced a giant jacuzzi pool. The pressure behind the pipe's narrow opening created two fast flowing whirlpools of hot spring water. Again the lead is problematic, but the overall design and execution puts many of our attempts to shame. Keep in mind that this is a public bath set up in a far flung Roman outpost town. The public bath in Rome itself could apparently handle 15-20,000 folks daily.

2,000 year old brick, and I was allowed to touch it! Notice the scored marks that my fingers are running across. Those marks provide a rough surface along the outside for mortar to tooth into better. These scratchings also served as a means to identify which craftsman made which brick, because each worker who have his own pattern. These signatures helped ensure correct payment for work completed, quality control, and a means of hanging out your shingle. Craftsmen working closer to Rome are known for using elaborately etched rolling pins to stamp and score their work with ornate designs. Beautiful designs that ultimately got covered up in a bed of mortar.

These particular bricks were used in the ceiling. Their hollow nature helped lighten the roof load and also created an effective thermal break that helped keep the bath's interior hot even in the winter. Two thousand year old brick! Let us begin building with the hope that the brick we lay will captivate and encourage those who come after us another 2,000 years from now!